The Met Gala, fashion’s most decadent and theatrical evening, has never been shy of spectacle—or symbolism. Yet as we prepare to drink in the visuals of this year’s theme, “The Garden of Time,” an undercurrent of discourse rises: if dandyism defines the aesthetic tone of the evening, could this be fashion’s soft-spoken attempt at reparation?

To suggest that the Met Gala, with its $50,000 tables and diamond-studded staircases, could serve as a platform for reparative justice may seem improbable. But fashion has always thrived in the liminal space between artifice and authenticity. And when it comes to dandyism, what appears at first to be mere indulgent elegance is actually rooted in histories of subversion, resistance, and reclamation—especially for marginalized communities.

Dandyism is often misremembered as the province of European aristocracy: pale men in powdered wigs and velvet coats, posing in parlors. But this lens is far too narrow. To dress as a dandy—particularly as a person of color, as queer, as othered—is not simply to peacock. It is to confront a world that says you do not belong, and to say instead: I define the terms of beauty, of presence, of power.

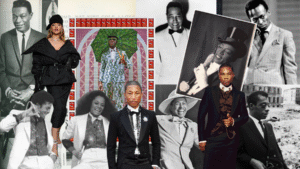

From the Congolese Sapeurs, whose flamboyant suits thumbed their noses at colonial rule, to the Harlem Renaissance figures who turned three-piece suits into acts of cultural sovereignty, Black dandyism is deeply political. It’s a lineage of elegance used to defy marginalization. Even in modern expressions—from André Leon Talley’s voluminous capes to Billy Porter’s red carpet architecture—the dandy is a rebel with a finely tailored cause.

And so, when the Met flirts with dandyism, knowingly or not, it wades into a current that is far older and deeper than European decadence. The question is not whether dandyism belongs to the marginalized—it always has. The question is whether this year’s Gala will acknowledge that legacy.

The fashion industry has long mined the cultures of the oppressed while ignoring their authors. From the adoption of streetwear to the co-opting of ballroom culture, from Indigenous beadwork to Caribbean flair, global fashion owes a staggering debt to non-Western, non-white, and non-cisnormative style. That debt is rarely paid, and even more rarely credited.

So could this theme be a quiet nod toward reparative acknowledgment? Perhaps. But only if the execution matches the implication. Who is invited to the Gala? Who is on the red carpet, not just walking but being seen? Which designers are spotlighted—not just worn, but named? Reparations, after all, are not just about symbolism; they are about access, agency, and authorship.

This year’s Met Gala offers the fashion world an opportunity to engage with its past and its present. Not in the form of apology, but in recognition. Not in performative inclusion, but in transformative celebration. If dandyism is the frame, let it be a mirror—reflecting the true origins of elegance as resistance.

And if we’re lucky, amid the sea of brocade and drama, we’ll see more than beauty. We’ll see history, reclamation, and maybe—just maybe—a glimpse of fashion’s overdue awakening.

SOURCE

Black Bride

Indulge Express

The Metropolitan Museum of Art